ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY PRESS INFORMATION NOTE

EMBARGOED FOR 00:01 BST, TUESDAY 17 APRIL 2007

Ref.: PN 07/ (NAM)

Issued by RAS Press Officers:

Robert Massey

Tel: +44 (0)20 7734 4582

Mobile: +44 (0)794 124 8035

E-mail: rm AT ras.org.uk

AND

Anita Heward

Tel: +44 (0) 1483 420 904

Mobile: +44 (0)7756 034243

E-mail: anitaheward AT btinternet.com

RAS Web site: http://www.ras.org.uk/

RAS National Astronomy Meeting web site:

http://www.nam2007.uclan.ac.uk

CONTACT DETAILS ARE LISTED AT THE END OF THIS RELEASE.

Most of the matter in the Universe is not the ordinary kind made up of

protons, neutrons, and electrons, but an elusive "dark matter"

detectable only from its gravity. Like a tenuous gas, dark matter is

all around us - it goes through us all the time without us noticing -

but tends to collect in large quantities around galaxies and clusters

of galaxies and makes up about one-sixth of the mass of the Universe.

In his talk on Tuesday 17 April at the Royal Astronomical Society

National Astronomy Meeting in Preston, Dr Ignacio Ferreras of s

College London will present the maps of the distribution of "ordinary"

and dark matter in nine galaxies out to a distance of five billion

light-years from the Sun.

Dr Ferreras worked with Dr Prasenjit Saha (University of Zurich,

Switzerland) and Professor Scott Burles (Massachusetts Institute of

Technology, USA) to take advantage of a rare astronomical phenomenon

known as 'gravitational lensing'. The galaxies they studied

serendipitously lie in front of quasars, which are bright sources of

light at even greater distances. The gravity of the nearer galaxy and

dark matter distorts the quasar light, causing the quasar to be seen

as two or four images. The placement of these mirage images, studied

using new theoretical techniques in gravitational lensing, makes it

possible to measure the total mass and effectively gives scientists a

telescope for dark matter!

By analysing the starlight from the galaxies using stellar evolution

theory, it is possible to measure the mass of the stars they

contain. Combining these ideas with archival data from the Hubble

Space Telescope, Dr Ferreras and his colleagues were able to make

dark-matter maps.

Current theories of galaxy formation can explain some but not all of

these new findings. After the Big Bang, gas should have fallen towards

the centres of dark-matter halos, there igniting to form the stars

that go on to make up a galaxy. But why is there a higher proportion

of dark matter in more massive galaxies? And had these galaxies

already finished forming five billion years ago? These questions will

only be answered by future theories of galaxy formation.

CONTACT(s):

Dr Ignacio Ferreras

King's College London

University of London

Tel: +44 (0) 20 7848 2150

E-mail: ferreras AT star.ucl.ac.uk

NOTES FOR EDITORS

The 2007 RAS National Astronomy Meeting is hosted by the University of

Central Lancashire. It is sponsored by the Royal Astronomical Society

and the UK Science and Technology Facilities Council.

IMAGES:

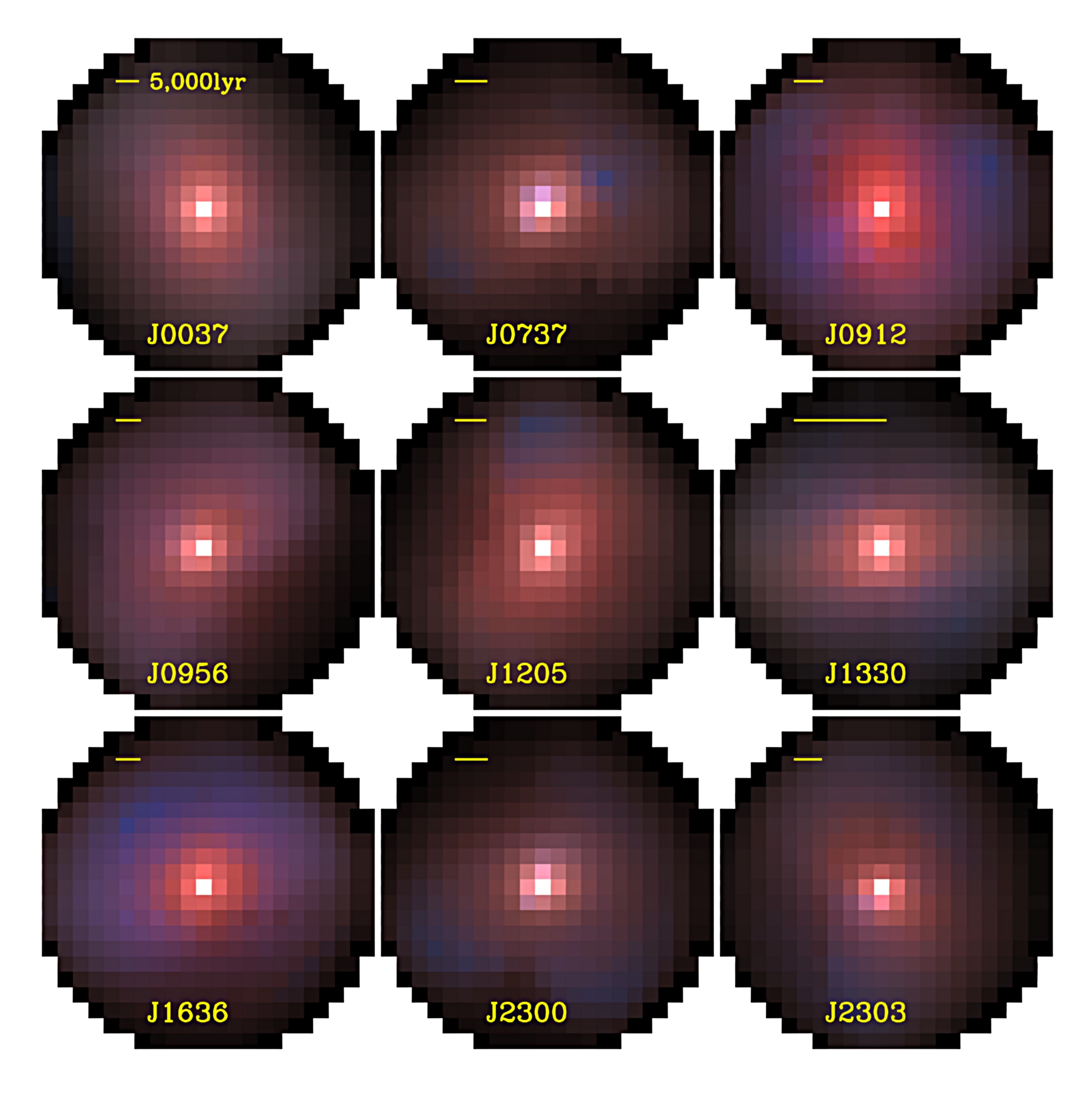

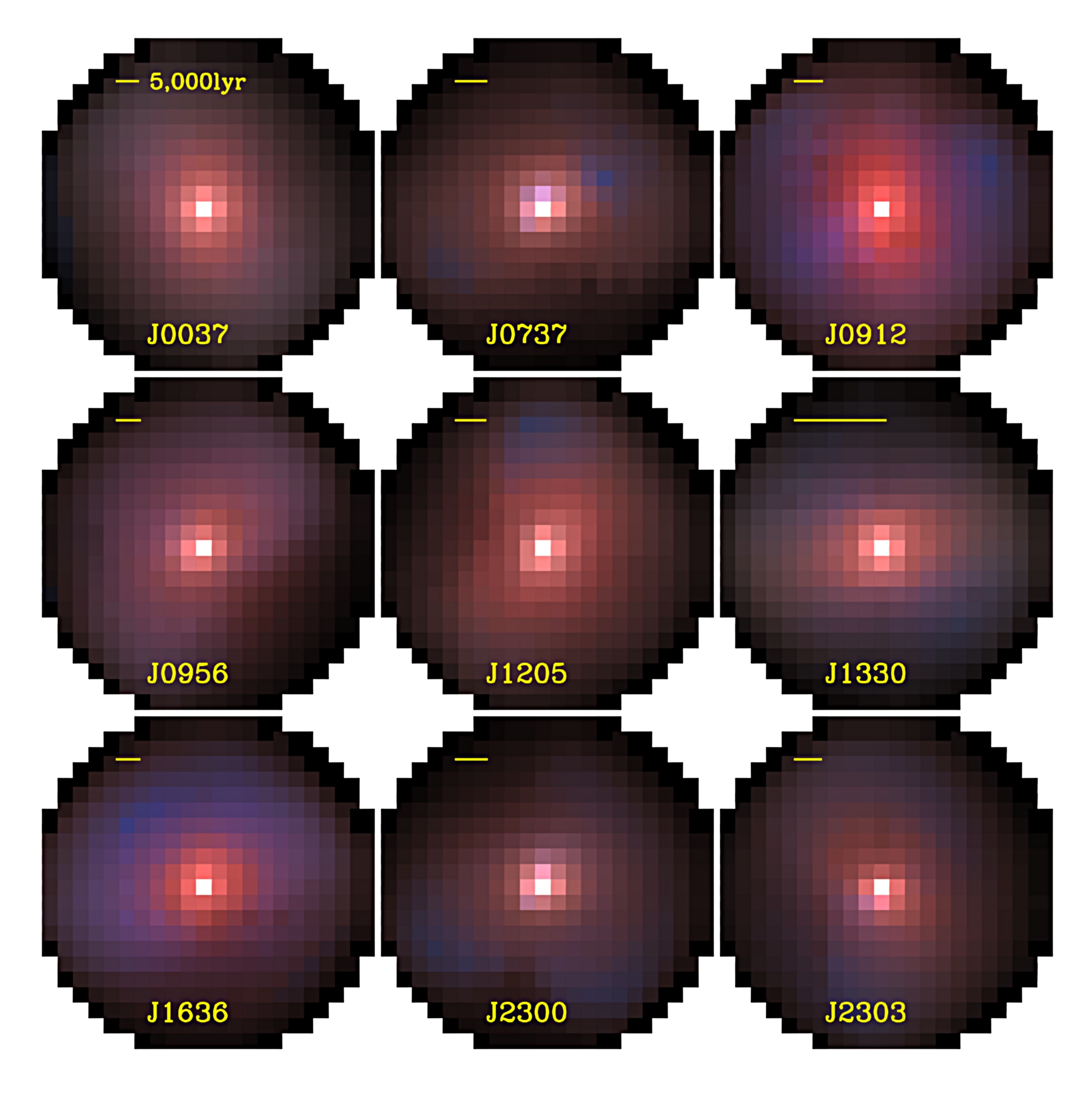

Figure 1. A false colour map of the dark matter distribution in the

sample of nine galaxies. The colour represents the ratio between total

and ordinary (or baryonic) matter so that dark matter dominates the

regions that appear blue, whereas in the red areas matter is mostly

baryonic.

|

|

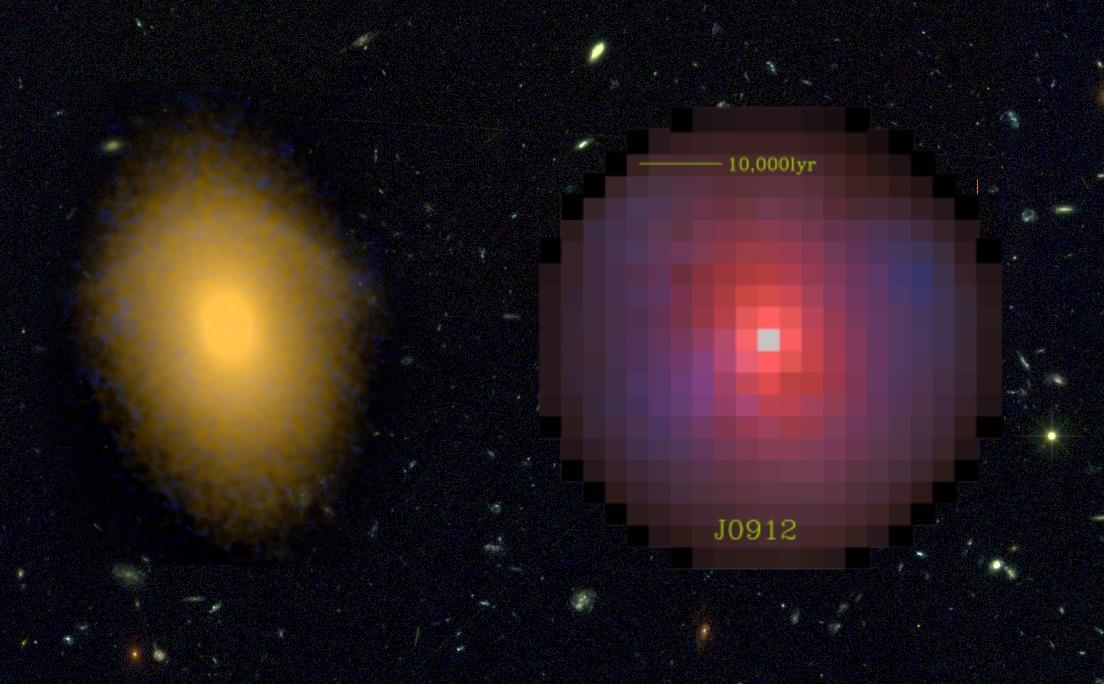

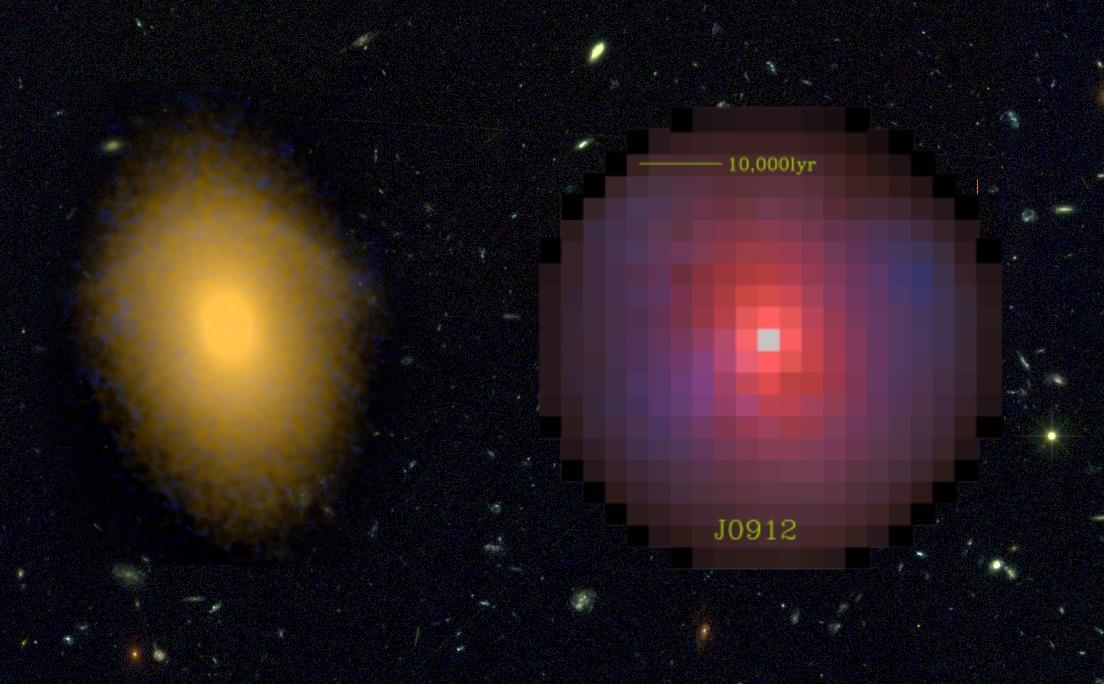

Figure 2. The relationship between ordinary and dark matter in a

galaxy. On the left is the ordinary matter that makes up the galaxy

and its shape indicates how it was assembled. On the right the map of

dark matter shows how it extends over a much larger area than the

visible part of the galaxy.

|

|

Figure 3. Gravitational lensing at work, illustrated with an image of

the old observatory at University College, London observatory. On the

left is the normal view and on the right we see it, as it would appear

if there were a massive but transparent galaxy hiding in the

quadrangle.

|

|